Re-thinking food safety: What kind of bread should we eat?

【Speakers】

Oates has been reporting on food safety and watching over the food additives market ever since the GMO food regulations were established in Japan.

Joan Bailey is a journalist specializing in food, farming, and farmers markets and also teaches about the intersection of food and culture.

******************************************

Bailey I teach a class called Eating Cultures at Temple University Japan where students explore their personal food cultures through a variety of topics. We look at everything from geology and climate to racism, Indigenous foods, and the role food plays in acts of defiance or revolution.

What we explore is the multitude of deep connections our food has to tradition, to place, to politics and economics, and more. I remind them that everything is connected. You can’t just pick out one thing and hold it up by itself. Food is inextricably linked to everything else even though we don’t think about it that way.

For example, my students often talk about how they are really concerned about health and nutrition, but they are also concerned about price. So they eat a lot of processed foods or just really cheap food because they are on limited budgets. I talk to them about why that food is cheap and convenient – things like price supports for non-organic farming methods and monoculture farming and the presence of things such as sugar, salt, etc., that make it undeniably delicious but quite possibly not very healthy.

I don’t criticize them for their choices because it doesn’t always feel like a choice, but I think they need to understand why certain things are more available, more affordable, and how that all ripples out from their food to the world around them and back again.

Oates Some 25 years ago, genetically modified foods (GMO) and farm products were introduced into the Japanese market. Many Japanese mainstream media outlets began reporting on import regulations, but only a few understood them or the GMO technologies.

Tsukuba University Bioethics Professor Darryl Macer was trying to encourage communication between corporate press officers and beat reporters about certain risks of GMO from a bioethics perspective. At the time, Japan was getting ready to import transgenic soybeans and corn.

Professor Macer expressed concerns about the safety and labeling of GMO foods as well as the lack of communication between businesses and media (and therefore, consumers), in a statement on how the science was applied to animals and farm products. This led to a mandated labeling of GMO products in Japan.

Bailey Is that when the restrictions came into being?

Oates The Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Ministry and the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry each handled the safety regulations concerning agricultural products and processed foods. They were confident about guaranteeing food safety as they each managed their own research institutes. At the same time, the safety assessment of GMO was already a well-established international system.

Consumers, though, were angry because the government made decisions about the regulations while ignoring consumer concerns. They completely mistrusted the government. Professor Macer was perhaps worried about this and thought the two sides – consumers and the government – should communicate better.

However, the more press briefings were held by the ministries or the companies — Monsanto or Novartis, as they are now called — and the more they explained about GMOs, the deeper consumer mistrust grew. Little has changed since then, and consumers still don’t trust the government.

Food-related incidents

Bailey Why do you think consumers don’t trust the government or the corporations? Was there any particular incident in the past concerning food additives or food safety?

People in other countries mistrust their governments about many things, but definitely about food additives. It makes me wonder if something specific happened in Japan that made people not trust the government and companies.

Oates One reason can be unclear labeling. Another reason is that there is only a limited space on products for labels. The ingredients are now indicated in bar codes, but they are still very limited.

Food additives were already in use in pre-war Japan. The current restrictions are based on those established after World War II, which is more than 70 years ago. Since then, we have also had a series of food safety cases in Japan. For example, PCBs, which are an insulation material for electronics, were detected in some foods, and arsenic was found in powdered milk.

When these cases were reported along with the names of the companies responsible, consumers were understandably upset. It’s also important to note that Rachel Carson in the US and Ariyoshi Sawako in Japan published books revealing more cases like this, not just related to food but the larger environment, and the dangers it presented. In the meantime, there were other cases where major pollution-caused illnesses like Minamata Disease, which was recognized with animals and people eating fish contaminated with mercury.

Bailey So there was a series of food-related problems.

Oates Yes, and these cases helped people realize that chemical substances exist everywhere in their daily lives. They also encouraged research on the potential risks caused by chemical substances, which resulted in stricter regulations on food additives. That’s why food coloring is limited, for instance, and the amount corporations are allowed to use has been declining every year. On the other hand, there have been cases where safety was confirmed after the use was legalized.

Bailey We also had a similar situation in the US. That’s some of what Rachel Carson wrote about in her book, Silent Spring. Published in 1962, it was also translated into Japanese in 1964 and helped fuel consumer activism around these issues. There are still food issues and concerns around chemicals and additives, and like here, people still find they need to pay attention to these topics.

Oates At least the US, EU, and Japan share food import regulations. You said earlier that culture or tradition defines food. I totally agree.

Even pickled vegetables – a traditional food in Japan — use food additives. Of course, no additives were used in the pre-war era. We use them now mostly to prevent food spoilage. I’m sure they don’t use additives for pickles as much in the US or the EU. We use close to zero additives at home.

Looking at food regulations

However, there are some wine additives that are used in the EU that are not yet approved in Japan. Similarly, there are additives for beef jerky that are widely consumed in the US. Unapproved additives were once used in Japan in the past.

So this means there are different demands in different countries with different food cultures. Testing for the safety of food additives is shared by Japan, the EU and the US. It is, in a sense, obvious that a country sets regulations according to its people’s taste buds.

“The shared regulations” means that each country has a similar basic framework and some consistency. The same goes for pharmaceuticals such as vaccines, like those for coronavirus.

Bailey What do you mean by setting regulations according to the people’s taste buds?

Oates Well, for example, we consume so little beef jerky in Japan compared to the US, so it’s no surprise if government officers didn’t see any urgency to confirm the safety of those additives. I remember from my childhood when my parents brought beef jerky back from Okinawa. They were told to dispose of it at the airport in mainland Japan. They were angry, but it just wasn’t allowed.

Bailey Sometimes I wonder why we can’t just have the same regulations. If it’s bad for people in the US, I assume it’s going to be bad for people here. It may sound naive, but why not?

Oates Some say that the tolerance level for certain ingredients among people in the US, the EU, and Japan is very different. That’s why the US or Japan conducts separate research even if the EU comes up with a result that shows some additives to wine are carcinogenic.

GMO food was first confirmed safe in the US, and transgenic corn and soybeans were later approved for planting in the US. But Japanese consumer organizations demanded that transgenic produce not be mixed with non-transgenic ones as GMO was not here at the time.

In the end, it appeared that Japan had to approve these GMO items in a hurry. Japan’s harvest season is fall. Even if safety is confirmed in the US, it needed to be tested in Japanese before the new crop was imported. Concerns were raised over soybeans and corn and whether GMO versions were used. The government needed to confirm whether it was safe for human consumption.

We use different soybeans, in the US and Japan, for instance. What Monsanto produces is not what we consume here. So soybeans imported from the US were clearly GMO versions or their hybrids. The import of US soybeans had to wait until their safety was confirmed in Japan; meanwhile, soybeans were imported from Canada.

I was at the Agricultural Ministry press club at the time, and I sarcastically asked the ministry official if there was a need to test the meat processed from animals raised on GMO feed. GMO corn was not allowed at that time, but it was indirectly brought into Japan. He was unable to answer the question.

Bailey The same thing happened in the US, and the government responded in the same way. But consumers didn’t believe them.

Oates In the 1990s, we also had Mad Cow Disease. Because Australian beef was grass-fed and wasn’t raised on bone meal, the cause of Mad Cow disease, Japan began importing more Aussie beef.

Flour Revolution

Bailey That makes sense. I wonder, though, other than GMO-related items, are there any food additives that people are concerned about in Japan these days?

Oates Although much of the Japanese media have almost completely ignored this, labeling of emulsifying agents in bread has been a big issue in recent years.

Consumers campaigned against some bread products claiming that it was dangerous because the company used yeast food, an additive used to grow yeast. Consumer advocates were so concerned that they said we should not eat it.

Bailey Do you mean industrially made yeast? For example, if you go to a store and buy a package of yeast, that’s industrially made yeast. It’s not sourdough, not natural. Michael Pollan, an American journalist and author of “Cooked” (2013), has pointed out that some problems are caused by industrial yeast as well as the industrialization of flour.

When these two things happened – the industrialization of yeast and of flour production – bread changed. There are many different types of wheats and flours, each having a different purpose or use. Some are better for bread or noodles, for example, while others are better for cake. When that happened, it changed bread and all the products into something else.

I think it was after WWII, when flour changed. Whole flour would go bad quickly as it had the germs. In order to give it a longer shelf life, you had to take the germ away and create the flour, which we now know as white flour. Now, it has a longer shelf life, but you lose all the nutrients. So those had to be added back in, which is where all of the additives come in.

With yeast products, white flour is nutrient empty, and the yeast is empty. It’s almost like artificially processed food at this point. For example, if you had sourdough starter, it interacts with wheat or flour in a different way. So people who have allergies, sometimes can eat sourdough bread without much reaction to it. It seems like there is research going on at the moment, but I don’t know how much is proven.

Photo: “Oates & Joan Bailey”/ Unfiltered

Photo: “Oates & Joan Bailey”/ UnfilteredOates We can say the same thing for Japanese grains, but we would suffer from a nutrient deficiency if we ate mainly white bread as white flour doesn’t have the germ. Tocopherol, which is one of the nutrients, contains mainly Vitamin E and comes from the germ that’s removed during milling. When you add Tocopherol artificially like this, it is considered nutrient enrichment. Because it is a nutrient that is already contained in wheat, you are not required to indicate it in the label. Baby food or cereals do not need to specify it in their labels if they are also categorized as nutrient enriched food.

Bailey What are some food additives in Japan if yeast food is considered a problem?

Oates Bread makers perhaps wanted to avoid indicating emulsifying agents. Japanese bread is very popular in Asia, and the emulsifying agent is one reason for that. Japan has very highly developed technology for emulsifying agents. It helps create that doughy texture that Japanese bread has. Consumers don’t know whether it is safe to see the emulsifying agent on the label, or whether it is safe to see yeast food instead.

Bailey I hear about this all the time. I have to admit it drives me insane because that is a signal of how much the food is processed. I’m not saying I don’t enjoy it sometimes, though!

It’s also interesting that you and Hibino-san were discussing carbon neutral and energy renewables for Unfiltered. If they have advanced technology for emulsifying agents and use it, why aren’t they using it for renewable energy?!?

But why are people especially worried about emulsifying agent?

Oates The problem was not the use of emulsifying agents but that some bread makers started to indicate, “there are no emulsifying agents or yeast foods used.” Of course, they need to substitute an emulsifying agent with something else that doesn’t need any indication. However, emulsifying agent or yeast food written on the label gives consumers the wrong impression that the bread is inferior or dangerous. In the end, the misleading labels that indicate the quality of products were banned by the Consumer Agency after some consumer groups protested specific bread makers.

There is a guideline set for the legal amount of yeast food, so there should be no problem as long as the amount was kept within the legal limit. The consumer group even conducted a comparative experiment to show whether bread grew moldy or not in order to show that the bread that didn’t grow moldy is not safe. As you know, you can keep bread mold free as long as you can manage the germ.

Is it specific to Japan to feel comforted or relieved to see the label saying, “No XX used?”

Read next

Event Announcement: Unfiltered AAJA Journalism Symposium in Tokyo

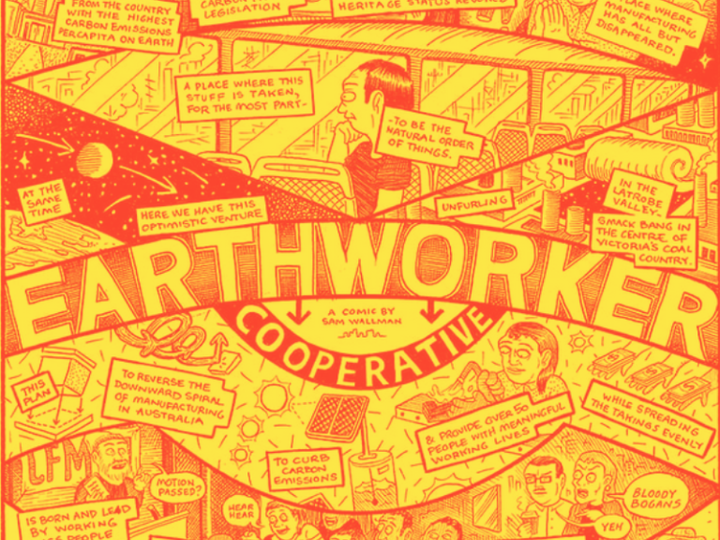

The Worker Cooperative Movement and Crises of Our Times