Dirty Fight

Tokyo has created one of the world’s best sewage-management systems but unions warn of the impact of market-driven capitalism and climate change.

Tokyo has created one of the world’s best sewage-management systems but unions warn of the impact of market-driven capitalism and climate change.

You might have missed it, but the UK is awash in shit, and not just the political kind. Britons have been warned to shun 83 beaches because of raw sewage. The Environment Agency says untreated sewage was dumped into British rivers and seas about 375,000 times in 2021. Environmentalists blame underinvestment in treatment and filtering systems (the result of privatization, they say), and the growing impact of climate change. Britain’s sewage system allows both rainwater and discharges from toilets to be carried in the same pipes to treatment plants – but the country’s creaking system can be overwhelmed by heavy rain and flooding.

Stinking sewers of Tokyo

Sewage management is a vital and overlooked component of civilization, which is why Britain’s mismanagement seems so shocking. Poor wastewater treatment went hand in hand throughout history with disease and death. Until the modern era, great rivers such as the Thames in London and the Sumida in Tokyo were stinking sewers. For millions of Londoners, morning began by opening their windows and tossing the contents of their ‘chamber pots’ out into the street, where it subsequently ran along shores and ditches to join larger bodies of water. Outbreaks of cholera and other water-borne diseases killed thousands of people in fast-growing European cities throughout the 19th century.

‘Honey trucks’

Tokyo today is seen as one of the cleanest megacities on the planet, and its high-tech toilets in particular are famous, but it wasn’t always so. Until the construction boom that preceded the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, only 20% of homes in the city had flush toilets. All night, reeking vehicles known as kumitoriya – dubbed ‘honey trucks’ – crisscrossed the city’s 23 wards, vacuuming sewage from underneath houses and transporting them to surrounding prefectures for use as fertilizer. Some sewage was simply towed out of Tokyo Bay and dumped into the Pacific. Methane gas bubbled up in the Sumida River. Only 30% of the Japanese population had access to safe water. Infant mortality was high and outbreaks of gastrointestinal diseases were common. An estimated 40% of the Tokyo population had tapeworms.

For years, the city’s exploding population threatened to overwhelm its natural resources, particularly its warren of narrow rivers and streams. Fixing that required human intervention and complex engineering – but it didn’t come cheap (the 1964 Tokyo games, for example, cost about 10 times more than the Rome Olympics in 1960 and began Japan’s addiction to issuing bonds to pay for construction projects.) But it did kickstart a transformation in the world’s most populated metropolis.

Pollution scandals of the ‘70s

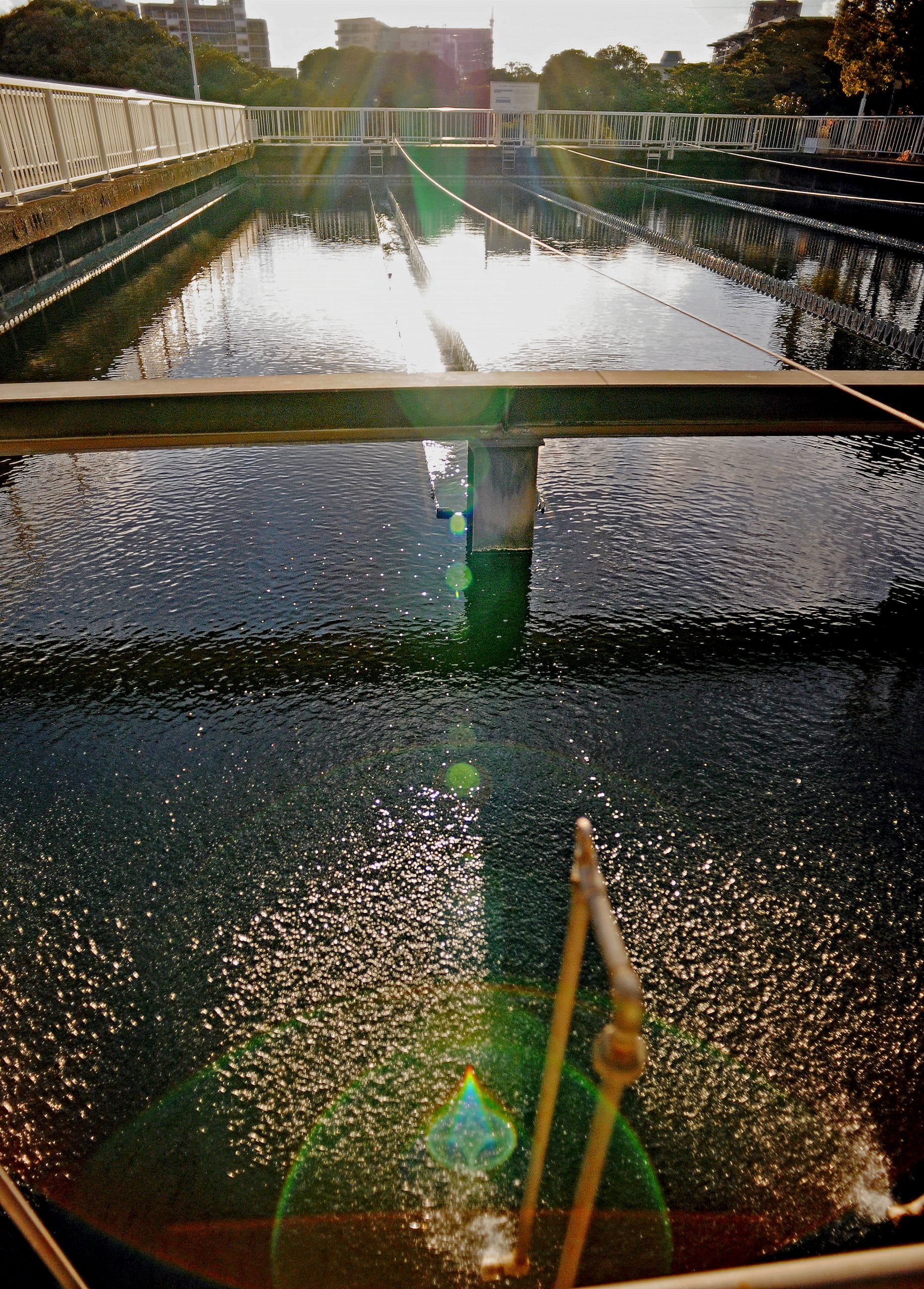

Over 16,000 km of sewage pipe was laid under the city between the 1960s and 1980s. In 1970, under pressure following a string of pollution scandals (including Minamata), the Diet passed legislation mandating tighter regulation of air and water. Regulating authority was ceded to local governments in the 1970s, giving those governments the power to radically improve their own sewage systems. By 1995, virtually all of the city’s toilets were connected to the system. A landmark of this transformation is the Morigasaki Water Reclamation Center, built in 1966, which today treats sewage for about a quarter of Tokyo’s area (14,696 hectares) – Ota City, most of Shinagawa, Meguro and Setagaya, and some of Shibuya and Suginami. The plant is one of the biggest in East Asia. Every day, a river of waste – 120 million square meters of sewage a day – is pumped into this facility.

Morigasaki works like a giant digestive organism, pushing water through a series of filters (including a grit chamber) that remove first solid waste, then settling tanks where solids are separated from lighter waste. Microorganisms such as bacteria (prokaryotes), protozoa (eukaryotes) or single cellular organisms, and more complex metazoa then feed off the waste in the reaction tank. For example, tardigrades, a microscopic, bear-shaped metazoan, process sludge while the simpler organisms consume fats, carbohydrates and other soluble material. Sludge is heated and digested in this process

helps provide 30% of the electricity for the plant. A final process uses sand and membranes, then a method called anaerobic-anoxic-aerobic to remove nitrogen and phosphorus from the water. By the time it flows into Tokyo Bay, you could nearly drink the water, jokes Harada Toshio, who has worked at the plant for about half a century.

Union’s work

Harada is one of the small army of workers – largely unheralded – who keep this treatment plant and 12 others humming in Tokyo; who lay and replace pipes, maintain the sewage system and fix any problems. “Workers on the ground have kept this sewage system running for the past 100 years,” proudly notes Kubo Akira, deputy secretary of the Tokyo Water Bureau Union. But he warns that government cost-cutting – in combination with the impact of climate change – threatens to overwhelm much of this good work. “In recent years, Tokyo has been experiencing flooding and overflow of sewage,” he says, blaming what he calls “guerrilla rainfall” – unexpected and sometimes unseasonal torrential precipitation. During Typhoon Hagibis in 2019, for example, flood levees were breached along the Tama River, which snakes over 138km through Tokyo and Kanagawa Prefectures. Similar flooding will become ever more frequent.

Japan’s central government wants to encourage local governments to privatize sewage systems and other infrastructure. Maintaining such infrastructure cost 2.6 trillion yen in fiscal 2013 and could be double that by next year, according to the Nikkei newspaper. The government wants to expand so-called private finance initiatives, or using private money to pay for public infrastructure, which have been widely implemented in the UK – often to disastrous effect, say critics. One impact, predicts Kubo, will be outsourcing and reducing staff. This is not new – Tokyo’s governor Suzuki Shunichi, who ran the city from 1979 – 1995, slashed the city’s workforce, he recalls – but it comes at an especially dangerous time, he warns.

Fighting privatization

“Private companies prioritize profit over water management,” says Kubo. “Cost reduction often ends up causing a deterioration in working conditions for employees, so the turnover of human resources is high. The skills and experiences do not get passed onto the next generation of workers.” Every worker left behind has to carry a bigger burden, which causes more to quit – a vicious circle, Kubo says.

Photo: Oates/ Morigasaki Water Reclamation Center in Tokyo

Photo: Oates/ Morigasaki Water Reclamation Center in Tokyo